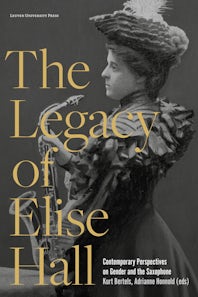

On the 100th anniversary of her death, The Legacy of Elise Hall–now available from Leuven University Press– provides a new outlook on Hall’s life and legacy as one of the major performers and concertizers of the saxophone. In various dissertations, articles and books, most writing on Hall has been colored with misogyny, talks of her clothing and insults to her gender. Her actual accomplishments get distorted or ignored. This book is the first attempt to provide a new perspective on Hall’s influence on women, saxophone repertoire, and how gender influences the saxophone’s portrayal in popular culture. The editors Kurt Bertels and Adrianne Honnold offer an interdisciplinary approach to examine Hall’s legacy by incorporating scholarship on gender, performance, and class in order to understand how her identity shaped and redefined the history of the saxophone.

Dr. Andrew J. Allen, in his chapter, “Incomparable Virtuoso, a Reevaluation of the Performance Abilities of Elise Boyer Hall,” sources the distorted opinion of Hall’s playing to Frederick Hemke’s 1975 dissertation, “The Early History of the Saxophone” which he describes Hall as an amateur and that she lacked technique. Because of these ahistorical takes, we often only see Hall as a commissioner of saxophone music, but not as an accomplished saxophonist. Allen corrects this record by focusing on her career as a soloist. As the president of the Boston Orchestral club, she brought to the stage new works never performed in the United States, including Bizet’s L’Arlesienne, Suite 1 where she played the saxophone solo. In Paris, she performed Vincent d’Indy’s Choral Varie at the Camille Saint-Saëns founded Société Nationale de Musique.

Hall also was the first woman to play with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, for their performance of L’Arlessiene in 1910. For the review of this performance, they ask the question, “Why should there not be women in our leading orchestras, if they are proficient?” There is a hint of suffragist language, noting the gender breakdown at major orchestras. These accomplishments as a soloist in major orchestras, her cross country music concerts, and her international performances in Paris have been overshadowed by her gender.

In Kurt Bertel’s chapter, “Paying and Playing? Elise Hall and Pratronage in the Early Twentieth Century,” highlights the wealth of music associated to Elise Hall. Since there was a lack of saxophone repertoire during lifetime, she commissioned works, mainly from French composers, to create chamber music for the saxophone. The chapter highlights the difficulty in knowing if Hall paid for these works, and how much money she spent. It provides a definitive list of the works written for her and the location of the scores.

Adrianne Honnold’s chapter, “Exhuming Elise, Rehabilitating Reputations” dives into how gender often distorts our view on Hall and other women performers. Since Hall was married, a woman, and a saxophonist, she did not have the means to be seen as a professional musician. The saxophone was never a part of the orchestra, and women of her class did not play music seriously, it was only seen as a hobby. This places Hall outside of the expected role for a woman of her class and position. Hall’s wealth and power gave her the freedom to pursue performing as a profession. Honnold goes further to compare the difficulty in assessing the term amateur vs. professional. What makes professional saxophonist in the early 20th century? That is not easy to answer. In the early 20th century, there were no professional women musicians because women could not be professionals, only amateurs. These terms we use categorize players has a way in tokenizing women and peoples of color contribution’s to the instrument. This chapter provides critical theory background for anyone engaging in projects that revolve around race, gender, and nation.

Sarah McDonie’s chapter, “Instruments Telling History; Engaging Elise Hall through the Saxophone” deals with Hall’s legacy and how saxophonists today are influenced by her work advocating for the saxophone. Since Hall was never a teacher and her commissioned works rarely get played, she did not create a musical lineage so her works are boxed in by history. A side note, one of the reasons her commissioned works rarely get played is the fact that many are out of print, and most are for chamber ensembles with saxophone. Until we create piano reductions, which is the majority of our teaching repertoire, these works will remain in the archives. Hall’s legacy as a “lady saxophonist” has influenced countless modern day saxophonist who see her as an inspiration and are following in her footsteps of advocating for the saxophone.

In Sarah V. Hetrick’s chapter, “He puts the pep in the party,” Hetrick’s analyzes how Buescher advertisements in the 1920s helped solidify the idea of the saxophone as a white male dominated instrument and that playing the instrument will draw attention from women. These ads changed the image of the saxophone, and that image of the saxophone as a purview of white men still remains dominant in today’s professionalization of the instrument. But the instrument always was played by women, as the next chapter demonstrates.

The final chapter, “Intersections of Gender, Genre, and Access, the Enterprising Career of Kathryne E. Thompson” focuses on the legacy of Kathryne E. Thompson. Holly J. Hubbs examines Thompson’s life a saxophone performer, pedagogue, and composer. This chapter is what drew me to this book, as I wrote about Kathryne Thompson for my doctoral degree. You can read my research about her life, I posted it under About Me. This chapter is the first published work on Thompson’s life, it’s an important corrective to the history of the saxophone that demonstrates women were active performers and teachers and pioneers in new technologies like the radio before the instrument was professionalized in the coming decades.

Overall, this book demonstrates how we have only just started to understand how gender influences the perception of the saxophone. The lack of professionalization of the saxophone in the symphony orchestra opened the door for women to take up the instrument. Elise Hall is the one of the most well known women saxophonist, but she is just one among many.