In the saxophone world, I sometimes hear saxophone professors proclaim ideas that are based on questionable knowledge of the history of saxophone literature and performance practice. After recently hearing from not one professor, but two, that Jacques Ibert’s Concertino da Camera is bebop I feel the need to provide a quick refresher of the relationship between Ibert and jazz. Concertino da Camera was written around 1933-1935 in France. Bebop evolved out of musical experimentation by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and others at jam sessions in Mary Lou Williams’s apartment and in clubs like Mintons in New York in the early 1940s. Saxophonists who say that the Concertino is “bebop” are unclear as to what they are referencing. I’ve heard “this line is bebop,” or the bebop line when referencing a particular passage. But calling it bebop, as it showcases certain aspects that become bebop language does not make a particular solo bebop, it’s merely a coincidence. One of the reasons I object so profoundly at this historical revisionism is by proclaiming a French composer writing bebop lines 10 years before the invention of bebop distorts and bastardizes the origin of bebop which is an African American art form. Now while many of the inventors of bebop were fans of impressionistic music, most notably Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite, Ibert does not seem to be a major influence among Parker and others.

What can we learn about the origins of Concertino da Camera that stay true to the historical influences? We have to turn to ballet to truly understand where Ibert was coming from. During the same period Ibert was composing the Concertino, he was also composing the ballet Le Chevalier Errant for Ida Rubenstein, one of the leading performers in Paris during the interwar years. Many of the works written for her have become some of the most popular works from this period including Ravel’s Bolero. Ibert had already written a ballet for her called Diane de Poitiers. Le Chavelier Errant, was the follow up to Diane de Poitiers but it never received its premiere with Rubenstein; it was resurrected in 1950 at the Paris Opera with Serge Lifar as the choreographer.

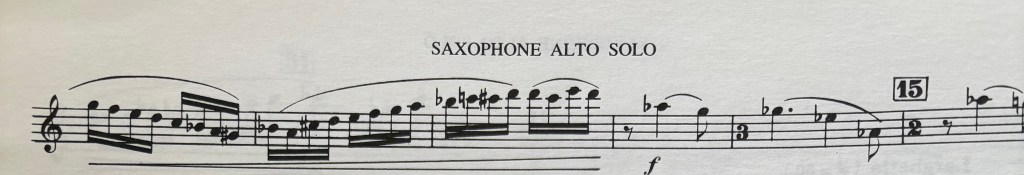

In the catalogue of Ibert’s work, the saxophone solo featured in Le Chavelier Errant was written in 1931, titled “L’Age d’or.” It appears he wrote the saxophone solo before he wrote this ballet which dates around 1933-1935. This is the third movement from the suite. The saxophone solo starts at 1:48.

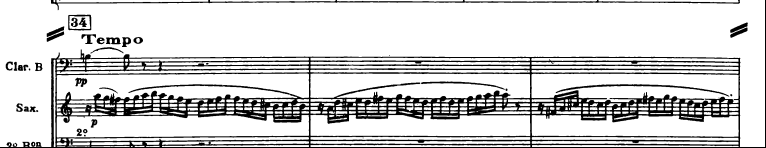

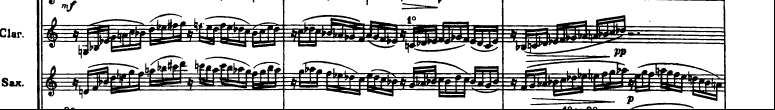

The alto saxophone solo starts out as a lyrical melody, before accompanying the rest of the orchestra in a 16th note pattern, starting at 3:23 in the above video.

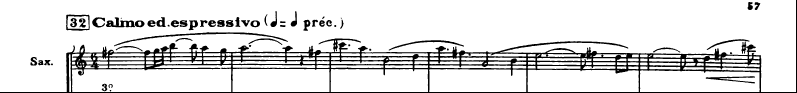

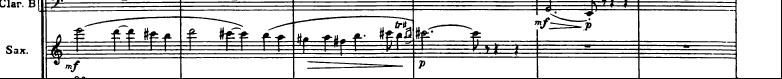

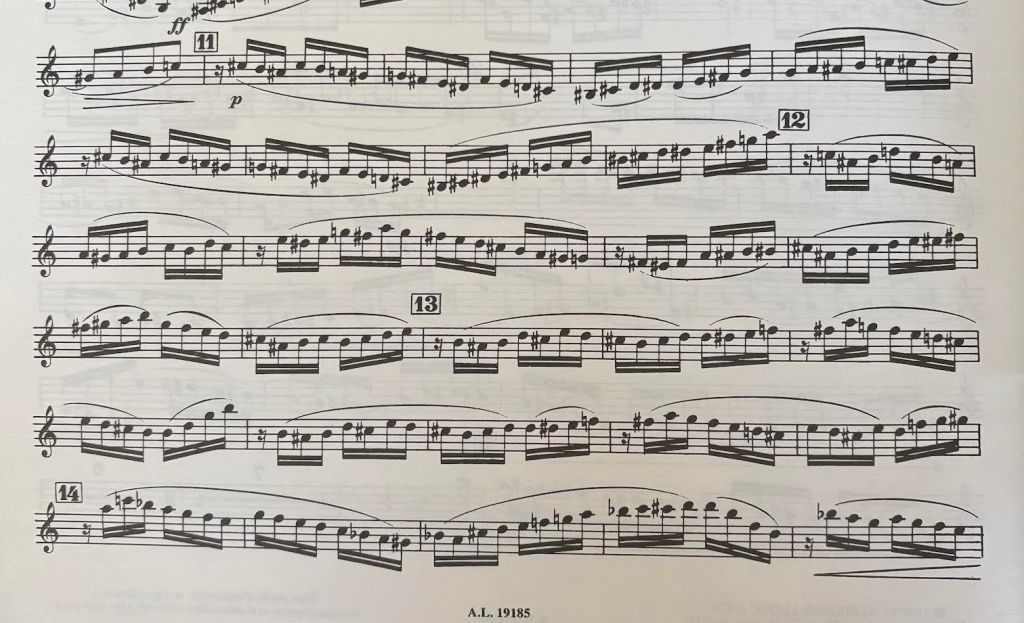

Now I have to admit, this movement surprised me. If your only knowledge of Ibert is the Concertino da Camera, this movement is lush and impressionistic, this solo is followed by the flamenco guitar. The writing is cinematic, with only hints of neo-classical style. Now comparing the above solo to Concertino da Camera showcases many similarities and a few noticeable differences. Below is the section that often gets compared to bebop.

First off, the solo in “L’Age d’or” is a six beat pattern versus an eight beat pattern in Concertino. The melodic line is inverted in Concertino where most of the phrases start with a downward motion. The biggest difference between the two is the tempo. The saxophone in “L’Age d’or” floats above the orchestra while the saxophone in Concertino da Camera is a relentless whirl of sound underneath the orchestra. But where what they have in common is more important. Both solos are a background figure to the orchestra despite being a solo instrument. Both solos have the saxophone play a lyrical melody before becoming an accompaniment to orchestra while the orchestra plays the melody the saxophone introduced. Both solos starts on the second 16th note of the measure, creating rhythmic tension and unresolved motion. Upon listening to “L’Age d’or” its easy to see how Ibert took this idea and developed it in Concertino da Camera.

The next question is what inspired Ibert to compose “L’Age d’or” in the first place? From 1929-31, Maurice Ravel composed his Piano Concerto in G. In the second movement, the piano plays an introspective lyrical solo that is abruptly interrupted by the flute and rest woodwind section. When the orchestra takes over the main theme, the pianist moves to an 16th note figure over the orchestra, 6:00 mark in the video below. Listening to “L’Age d’or” and the Concerto back to back, its easy to see how “L’Age d’or” is an attempt by Ibert to experiment with Ravel’s melodic interpretation.[1]

Ibert using this solo as a jumping off point for “L’Age d’or” makes a lot of sense when he wrote this solo the same year this concerto was completed. Ibert never published this solo until 1956 so based on the published dates, one might think Concertino da Camera came first. This solo is just not as well known to the saxophone world. And the ballet Le Chavelier Errant is a rare work that by my count only has three recordings in existence. The rarity of these works, it’s easy to understand why they don’t get mentioned alongside Concertino da Camera. The correct order of events is Ravel’s Concerto in G,—“L’Age d’or”–Concertino da Camera. The Concertino is not bebop and could never bebop, given that it preceded bebop by several years; it’s inspired by Ravel.

Edit: “L’Age d’or” copyright date is 1956. A previous version of this post had that at 1946.

[1] Jacques Tchamkerten. IBERT, J.: Chevalier errant (Le) / Les Amours de Jupiter (Lorraine National Orchestra, Mercier) 2015. Liner notes, pg. 10.

Leave a comment